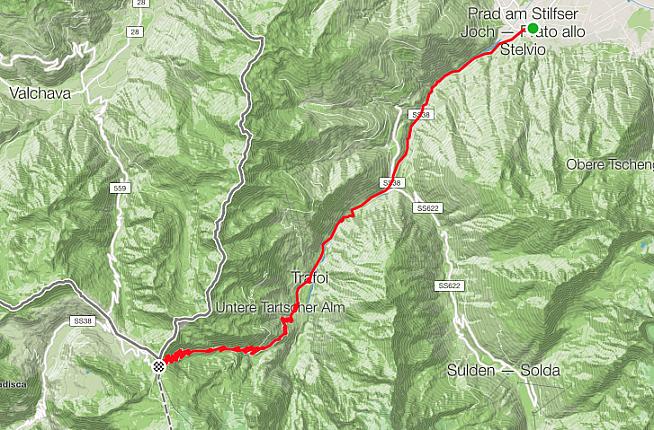

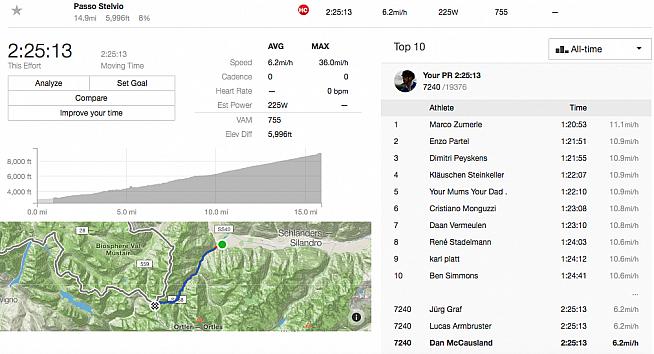

I rode up the Stelvio Pass.

I did not conquer it. I did not crush it or smash it or other silly verbs that suggest dominance.

I rode up it and that was enough.

Enough in fact, along with the spectacular lunatic-grin-inducing descent, to put the day into the top few rides I have done.

Those numbers don't come close, however, to capturing the awesome nature of the Stelvio -- the famous 48 hairpins, the feeling of zig-zagging up a vertical wall at the top of the valley, the peaks you end up level with at the top.

It almost didn't happen.

Waking up in the village of Prato Allo Stelvio on the day that had been ringed on the calendar hanging in NY State as "Stelvio Day - gulp" for many months, we had been greeted with torrential rain accented by occasional flashes of lightning and the accompanying crashes of thunder.

In retrospect it seems incredible that we ummed and ahhed about what to do for as long as we did weighing up HTFU and Rule 5 against sanity.

For me at least, it was not the going up and getting soaking wet that was the issue, it was the thought of a freezing descent on wet roads. And by wet I mean really wet. Rather than carrying it away, the drains in the village, the start of the pass on the eastern side, were dumping water onto the road outside our hotel they were so overwhelmed.

When a Google Translate of a term in the Italian weather forecast came back along the lines of "heavy rain that can fall as sleet or snow on a lee slope at high altitude" sanity triumphed.

After a rejigging of plans and the sacrifice of the chance of riding the beautiful Sella Ronda around Corvara we were back at the base of the Stelvio 24 hours later.

Clipping in at the bottom of any big climb that you are tackling for the first time always causes a flood of questions from the practical ("Am I in good enough shape?", "What did I forget?", Is Strava on?") to the anticipatory and even existential (How much is this going to hurt?", "Will I embarrass myself?", "Why are we here?", "Why am I doing this?"). Actually, the "Why I am doing this?" usually hits me after about 10 minutes in that horrible period after the legs and lungs have started to realize they have to work hard and before you have settled into the climb.

The relatively easy start from Prato Allo Stelvio meant that we found our climbing pace easily enough and soon the physical quieted the mental. Muscles warmed, lungs began to work, kit was adjusted and a rhythm was found.

The classic image of the Stelvio shows the final section on the Eastern side with the snaking hairpins climbing the steep wall to the top of the pass. It starts with less fanfare 15 miles and 6,000 feet below in a small V-shaped river valley.

The early sections, which are also the gentlest, give only the odd glimpse of the peaks above outlined against the sky as the river splashes next to the road.

It is not until you hit Trafoi with its cluster of hotels and alpine church after eight miles that the hairpins begin and from there it is turn after turn all the way to the last section where they cling to the near-vertical wall of the valley up to the pass itself.

Before that the grade is a consistent 7%-9% after the initial 5 miles around 4%-6%. Overall, the average is near 7.5%

The road is an amazing feat of engineering. It was designed to improve travel between Vienna and the Austro-Hungarian Empire's territories in western Italy. It took 2,500 workers from 1820 to 1825 to build it led by Carlo Donegani, who I imagine called for the schnapps bottle when he received the instructions for the job.

Since WWI, during which it was a battleground, the pass has belonged to Italy. Two of the routes to the top - the "classic" approach I did from the east and the Bormio route from the west - are in Italy the third, the Umbrail Pass from the north is in Switzerland until it joins the Bormio road around 200 yards from the top.

The Stelvio has featured in the Giro d'Italia 11 times with stage finishes on four occasions. Fausto Coppi led over it in 1953 when it was used for the first time and Charly Gaul did the same eight years later. It is one of the joys of cycling that you can ride the same tarmac as the stars of the sport. It really is the equivalent of batting at Yankee Stadium, playing the Old Course at St. Andrews or lapping the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. It is special.

And if you want to race it as an amateur, the Granfondo Stelvio Santini uses the Bormio ascent with the 151km Long Route also taking in the Mortirolo in its 13,313 feet / 4,058 meters of climbing in June each year.

It was above Trafoi on the first of the hairpins that Joe, my riding companion, encouraged me to head off on my own as he was having a bad day and didn't have his climbing legs with him. When riding together we've always worked on the basis that climbing should be done at your own pace. It's always his skinny frame leaving my heaving carcass behind so I pushed on enjoying the novelty.

Unsurprisingly for a route once called the greatest driving road in the world by the Top Gear gang, as well as cyclists there were a good number of cars and motorbikes roaring up the pass. Those of us using pedal power to climb the pass must have been a slow-moving, very-slow-moving, chicane for the petrolheads, but we all co-existed pretty well.

I felt surprisingly good all the way up and made it without a stop. The final half an hour or so was a grind, but by then you can see the finish line high above you and I focused on reaching the next corner with every other bend swinging to the right and forcing me out of the saddle to keep up momentum through the steep inside of the bend.

As mentioned, the steepest average grade comes right at the top of the Stelvio at which point you've already spent (in my case) over two hours climbing and the air is noticeably thinner as well up near 9,000 feet.

I covered the last three or four hairpins with a wide grin on my face as the deep satisfaction of achieving the goal at hand masked the complaints from legs and lungs and irritations of salt-laden sweat in the eyes and dry mouth.

It was a very good feeling to reach flat ground at the top and unclip.

Zipping up my vest to its fullest I waited with one foot clipped in for three motorbikes to go past before releasing the brakes and enjoying gravity's effect.

After a couple of bends I slipped by Joe, who does not get nearly as much assistance from physics as I do and tucked low, hands on the drops.

Switching back and forth through the hairpins I realized I was catching the motorbikes. At the corners they had to slow so much - especially if there was traffic coming up forcing them to take a tight line - that their advantage on long straights was cancelled out by my speed in the bends.

Pretty quickly I was on the tail of a blue BMW touring bike with German plates. Coming out of each hairpin the rider would accelerate away and I would catch him again as he hit the braking zone for the following turn. I was having to brake harder than I would have otherwise and getting to within a couple of feet coming out of the bends. It was fun.

All of a sudden, the passenger perched on the back spotted me and there was a bit of tapping on shoulders and chat on the bike. On the next straight the road was clear and the bike pulled to the left and motioned me alongside in a flurry of waves and thumbs-ups. The pilot's English was better than my non-existent German, but sign language was the primary comms method along the lines of:

MC: Thumbs up -- "Hey!"

Me: Nod, wave and grin -- "Hello!"

MC: Shrug of shoulders, double-take, widening of eyes -- "Bit surprised to see you on my tail."

Me: Grin, shrug of shoulders -- "Just having fun."

MC: Thumbs up, thumbs up, wave of hand - "You go past, you crazy cycling idiot!"

Me: Thumbs up, grin - "You, sir, are a gent of the road, appreciate it, see you later!"

And see them again I did.

Below Trafoi where the road straightens out the benefits of the internal combustion engine came into their own and the BMW came alongside again. Through mime and a few shouted words the biker made it clear he wanted a photo with me and sure enough he was waiting near the bottom of the pass greeting me with handshakes, high fives and a leather-clad arm around the shoulder as his passenger snapped pictures.

That's never happened to me before and probably will never again. Stupidly I forgot to whip out my phone so I don't have my own pic, but it's something I won't forget in a hurry.

All in all, a pretty special birthday.

0 Comments