Some hills are famous ... but only mountains become legends. The Tourmalet, Alpe D'Huez, the Stelvio and, perhaps the biggest of them all, Ventoux.

The highest and most isolated mountain in France, Mont Ventoux has hosted nine summit finishes in the Tour de France - with winners including Merckx, Pantani and most recently Froome - and been featured six other times. The "Giant of Provence" stands 1,911m above sea level with winds of at least 90kph recorded at the summit 240 days a year.

It's also the mountain Tom Simpson died on during the 1967 Tour. A monument to his memory stands silently by the side of the rode close to where he fell from his bike almost 50 years ago. It's become a pilgrimage site for cyclists - leaving bidons, gloves, caps and other offerings to his memory as they ascend the mountain themselves.

I had to ride it. But if you're going all that way, why stop at once? Especially when there's a club, a closed club, to join. The Madmen of Ventoux.

The Cinglés Club

"In 1988 the Brotherhood of Madmen of Mont Ventoux was created to show that any normally trained cyclist could climb the 'Giant of Provence' by the three main roads to the summit in one day without excessive fatigue."

So reads the homepage of Club des Cinglés du Mont-Ventoux. Pure fantasy? I was about to find out.

I'd not done any special training, in fact I'd put on a couple of kilos since the Etape and the RideLondon-Surrey (a-bit-less-than)100. So "normally trained" was about right.

The rules of joining this club are simple:

- Ascend Mont Ventoux from at least three main roads: Bédoin, Malaucène and Sault. (There are other options, notably the double or "Bicinglette" (i.e. six climbs); adding the off-road route to the main three (Galérien); and then there's the man with the record - 11 ascents in a day.)

- The climb will be in the same day (but in the order and the date you prefer).

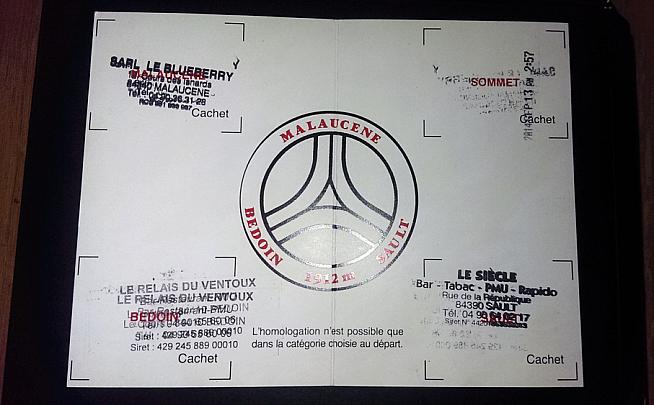

To prove you've done it you get a brevet card sent to you; this must be stamped in the three villages at the foot of each climb, and again at the top. That done, you send it off and get club membership.

Of course, simple doesn't mean easy. To complete the Cingles means more than 4,500m of climbing (and descending), up a mountain, in one day. A mountain where the wind reaches 320kph at the top - although they generally close the passes if that's the case.

On Saturday 13 of us, supported by the lovely people at Just Pedal set out to join this dubious club. Some succeeded.

Road 1: Ascent from Bédoin

It took 15 hours to get there the day before. That's 15 hours sitting, cramped, in a mini-bus, trying to sleep and eating. I ate a lot. And not the right things either. It wasn't ideal preparation for the most climbing I'd ever attempted in a day...

I woke nervous the morning of our attempt. The weather, which had been pretty awful for my last two big rides, looked a bit too perfect. Cool in the morning, mid 20s by lunch, teens in the early evening. The wind was low.

The cyclists gathered, nervous, outside the hotel for a pre-ride briefing which could be summarized as: "trust us, beware the wind, look at riders ahead of you for clues"; and out we rolled.

The Bédoin ascent is the one we're all familiar with from the Tour. 21km long, rising 1,617m. That's an average of almost 8%. For 21km. It takes in the Chalet Reynard and the Simpson memorial, and exposes the riders to the worst of the wind over the last 6km (which are also brutally steep in places).

Bédoin's a pretty village, full of bars and restaurants, and finding somewhere to stamp our cards and writing in our start times was simple. After a faff and much gesticulation (our French being worse than their English, and neither good) our cards were stamped and off we went.

The cafe in Bedoin where we stamped our cards.

The climb starts relatively gently. I was nicely warmed up by the 12k ride - a gentle climb - to Bédoin and full of food and liquid. I locked into Alpine Climbing Mode. Heart rate in zone 3 (c150-160bpm for me), I was working, but at a rate I know I can hold for at least two hours, cadence steady, keep going. Ticking off the kilometer markers as I went.

The road rises, gently at first, then about 6km in it ramps up. This is the infamous forest section. Protected from the wind, the road rises to average 9% for the next 10km, with entire kilometers averaging 11%.

You twist up the mountain, the kilometer markers mocking you with the hope of a slackening off, a break in gradient for a bit, merely for the next one to tell you the next kilometer averages 10%. And then again. And then 11%.

After a brief respite, where an 8% section feels like a descent, it gets worse.

I emerged from the forest and passed Chalet Reynard, 6km from the top, to the sound of a marching band playing. And also to a post-apocalyptic landscape of shattered rocks and a headwind.

The gradient is theoretically shallow (for this climb) at 7-8% for a few kilometers. The wind made it feel like 12%. I pushed on, and with 1,500m left dismounted for the first time in the ride. I'd reached Tom's memorial.

Tom

There's nothing I can write to add to what's already been written about Tom Simpson's life and tragic death. Some facts are simple enough. He was Britain's greatest cyclist, a world champion and Olympic medalist. He won three of the one-day monuments (the Tour of Flanders, the Giro di Lombardia and Milan-San Remo) and the world championships as well as the Paris-Nice stage race. He was one of the favorites for the 1967 Tour de France.

He collapsed on this road racing that Tour on July 13, was put back on his bike at his own request, collapsed again a few hundred meters further along and died of heat exhaustion.

A memorial to him stands by the side of the road where he fell. I got off my bike and walked to the top. Gently resting my bike against the steps I placed a king of the mountains cap I'd carried up the mountain with me at the foot of his memorial and weighed it down to protect it from the wind with a piece of Ventoux's blasted rock.

There were other mementos there already - some gloves, some socks, four bidons and a bottle of water. I left the cap alongside them, bid Tom farewell and got back on my bike to climb to the summit.

The summit for the first time

The end is hard, but that close to the finish you can make it. A vicious right-hand turn had my front wheel lifting off the tarmac as I rounded the very last corner out of the saddle... and I was there.

A time of 2:08 for my first ascent. Not good, but not bad either and I'd done it without any major problems

Gilet on, the descent to Malaucène was fast and technical. The mountain made many of the corners blind; it was steep, the roads were open to oncoming traffic. My brakes were getting a real workout.

I averaged more than 40kph down the mountain, topping out at almost 70. Quickish - but far slower than a lot of others, and comfortably in the bottom half of the Strava results.

It was also cold; not freezing or in "hands too cold to brake" territory, but certainly chilly. A couple of the UK riders in the group - new to Alpine riding - were taken by surprise and wore all of their spare clothes for the next two descents.

Road 2: Ascent from Malaucène

I took stock at a cafe in Malaucène, another very pretty village - and one with what appeared to be a dedicated Pinarello shop in it. Sitting in a cafe warming up after the descent, I ordered a coffee and got my card stamped.

I'd only drunk one bidon and had three gels on the first ascent. I swapped my full bidon for the empty one, and added a sachet of caffeine/energy drink to the plain water I normally keep in my second bidon.

I ate a bar and set off. I wasn't too worried about the lack of water, as I'd seen our tour operator's van three times on the last ascent and I could refill there or at Chalet Reynard 6km from the top if needed. I only had three isotonic gels left, but that was what I'd climbed the last one on.

It was a stupid, stupid decision. The temperature had risen by 10 degrees since I started the last climb, I'd burned off most of my pre-ride food and had a mountain's worth of climbing in my legs already.

But I wasn't the only one suffering.

Second time's far from charming

You can climb the three main roads to Ventoux's summit in any order to join the Cinglés. But most people ride them in order of difficulty, hardest first. This presents something of a problem because, while there's almost no debate on the easiest way up (Sault), the difference between the road from Bédoin and the one from Malaucène is tiny. Malaucène is a bit shorter (by about 1k) but starts a bit higher up (about 100m). There's far less cover on a hot day, but it is sheltered from the worst of the wind. Overall, there's not a lot to choose between them - except, of course, when I rode Malaucène it was hotter and my reserves were low.

The road gets hard, fast. 1.5k in and you're at 7%, 2.5k in and you're at 9% for the next 2km. Full of caffeine and thinking I'd gone a bit too easy last time, my heart rate was 10bpm higher than at the start of the Bédoin climb.

The heat was getting to me, and the caffeine in my bidon made the water hard to drink with a bitter tang at the end of a sip leaving me feeling a lot less refreshed. And I was drinking a lot to keep my energy up.

Just after the 7km in sign I stopped in some shade and took off my helmet. Paul, who rode with me for the first 15km of the first climb before dropping me, asked why.

"I need to cool down, and eat, and we're a third of the way up so it seemed a good time," I replied. He agreed. It wasn't the first time we stopped, alternating who pulled over to the side first.

The road was unforgiving and the heat relentless. I unzipped my jersey to my heart-rate monitor but there was no wind to cool me. Five kilometers in a row averaging in the double figures. A straight section of road, more than a kilometer long at over 10% that you just stared at, disbelieving. After the 12km to go sign, the 11km and the 10km to go one all said 11% or 12% for the next kilometer. I did some mental arithmetic.

800m of vertical climb left, 10km of road left... 8% then. We were due a break in gradient. Overdue a break in gradient. The slog with almost no water left had to end soon. The 9km to go marker appeared. Next km averages at... 11%.

"**** YOU!" I actually screamed at the road sign. Out loud.

Paul was cracking at this point, and in one of our increasingly frequent breaks he ripped off his jersey, stripped off his base layer and threw it to the floor. "I can't take it (the base layer) any more", he answered my unasked question.

Paul beat me by 8 minutes on the first ascent, I dropped him on the second.

Dry run

Water was becoming an issue. While I saw the support vehicle parked up by the side of the road three times on the first ascent, I hadn't seen it parked this ride at all. Nine kilometers of mountain is a long way to go on a hot day with only a single bidon of caffeinated energy drink.

I still had some left, but I wanted to drink a LOT more than I had. But it was only 3km to Chalet Reynard; I told myself that I could stop there if needed.

Except, of course, I couldn't. Because as I reached 6km to go I realized that Chalet Reynard wasn't on this route, it was on the other side of the mountain. It's the sort of little detail that apparently slips your mind when climbing in heat.

I was in trouble and I knew it.

Then, like a vision sent from the gods, with 5km to go the Just-Pedal van appeared. I waved frantically. It stopped and I just demanded water. Drank about a bidon worth and then demanded more.

It soaked into me like a sponge. I got a couple of gels from them which I downed as well. Refreshed and full of sugar I remounted to finish the climb.

I'd broken the back of it, the steepest and most unrelenting section is those middle kilometers. It had also almost broken me, thanks in part to terrible planning.

But the rest of the ride was simple. The final 5k averages 8%, with the slightly disheartening view of the famous weather station still seemingly high above you, but the road is never as relentless, as punishing, again. I crested the summit for a second time.

With breaks and dehydration included it had taken me half an hour longer than the first ascent.

The greatest descent on Earth (possibly)

I took a bit of time at the top, firstly to find our group (the van was in a different place), then to get some salt (via crisps) and Coke into me and don my gilet before heading down the mountain for the second time.

It's possibly the best road I've ever descended on. Once past the initial steep, fast, section the road surface becomes perfect. Perfect. Brand new smooth, black tarmac.

The road sweeps downwards with great sight lines on the corners, some gentle enough to take flat out, the vineyards and green countryside laid out like a picture to your left, then right. I almost forgot to brake for a corner as I was taking it in.

The gradient is shallow, 3-5% for most of it, rewarding sprinting from the drops as you exit corners and never out of control. One or two tighter turns for the technicians, and then the smell of lavender on the air as you near the bottom.

Quite simply perfect.

One more for the road: Ascent from Sault

At the end of the descent is a small climb into Sault. I stopped at another cafe with some of the group. I got my card stamped, drank a Coke and ensured that, this time, I had two full bidons - neither with caffeine in them.

I was out of gels, barring the couple of caffeine ones I had picked up from the van, but had some bars left. I ate one in the cafe chatting to other riders.

I had no ambitions to be fast up the final ascent, I just wanted to get to the top by any means necessary. I planned to stop a lot. Eat a lot. And ride within myself. Four of the hares who set off hard for the first climb had since broken. Slow and steady would win me this race.

There's a reason you tackle this climb last; well, two. Firstly it starts higher, meaning less climbing overall. Secondly, it's longer, meaning a shallower gradient.

A lot shallower. The first 20km of the climb is at a miserly gradient of 3.6% - you can spin it. And I did. The road surface and scenery was just as stunning as it was on the way down; my speed was low, I stopped a lot.

Along the way Ron and Skelly from the Just-Pedal group caught up with me. We rode the rest of the way together, the last riders from our group on the road, heart rate lower than on either previous climb, no strain through the legs, drinking and eating a lot.

The final 6km are identical to those on the Bédoin ascent. Hard, and exposed to the wind. But the wind had stopped, and the temperature had dipped since the hot second climb. We were spinning our way to becoming Madmen, ticking off kilometer markers, while chatting and laughing among ourselves.

Then, no more than 4k from the end, we were hit by the most innocuous but intractable mechanical I'd ever seen.

Ron's chain slipped, pushed behind his cassette, and jammed between it and the hub. Properly jammed. Everyone stopped to look, including members of our group descending the mountain having already become Madmen, and suggested exactly the same three solutions (myself included): "Have you tried taking the wheel off?" yes; "Have you thought about breaking the chain?" yes, it won't work; and, when they looked in detail, "We're going to have to take the cassette off..."

We were. Except who carries a lock ring removal tool on a ride? Or a chain whip? We were there for a while.

Eventually, as the sun began setting behind the mountain, our van turned up with the necessary tools. A minute later we were on our way again (we only needed to loosen the cassette by a couple of millimeters in the end).

Done

Without the headwind the final few kilometers of Ventoux are a lot less problematic. We spun, and then, with the summit a hundred meters away, sprinted to the encouraging shouts of the rest of our group.

Skelly was shaking, shocked to complete a ride he'd only signed up to three weeks before and not trained for at all, and crashing as he hit a sugar low. Ron was jubilant. I was, well, relieved. I came here for one reason, to ride up the mountain three times in a day. I'd done it.

All I had to do was find someone to stamp my card (using a machine, as all the vendors at the summit had packed up and gone home by this point) and not die on the descent to Bédoin and we were done.

I flew down the mountain, racing the sun; with no lights on the bike or the street and the road open to traffic, I was keen to go as fast as I safely could.

I lost, arriving in the start village in the pitch black, but alive. We stopped for some beers, put in a call, and waited be picked up for the drive to the hotel.

We'd done it. 150km riding to, then up, then down a mountain. Almost 12 hours in total, more than nine of them riding. A staggering 4,767m climbing - that's three miles straight up. All in a day.

Madmen indeed.

0 Comments